Introduction

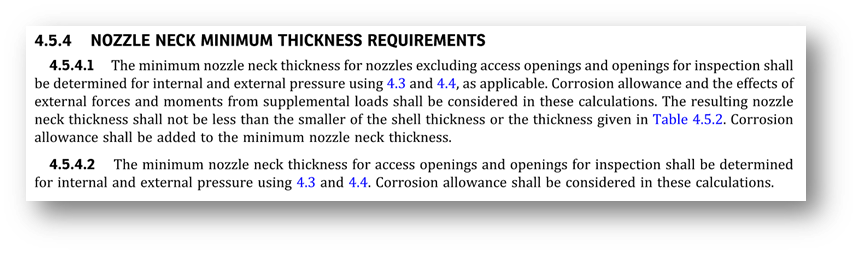

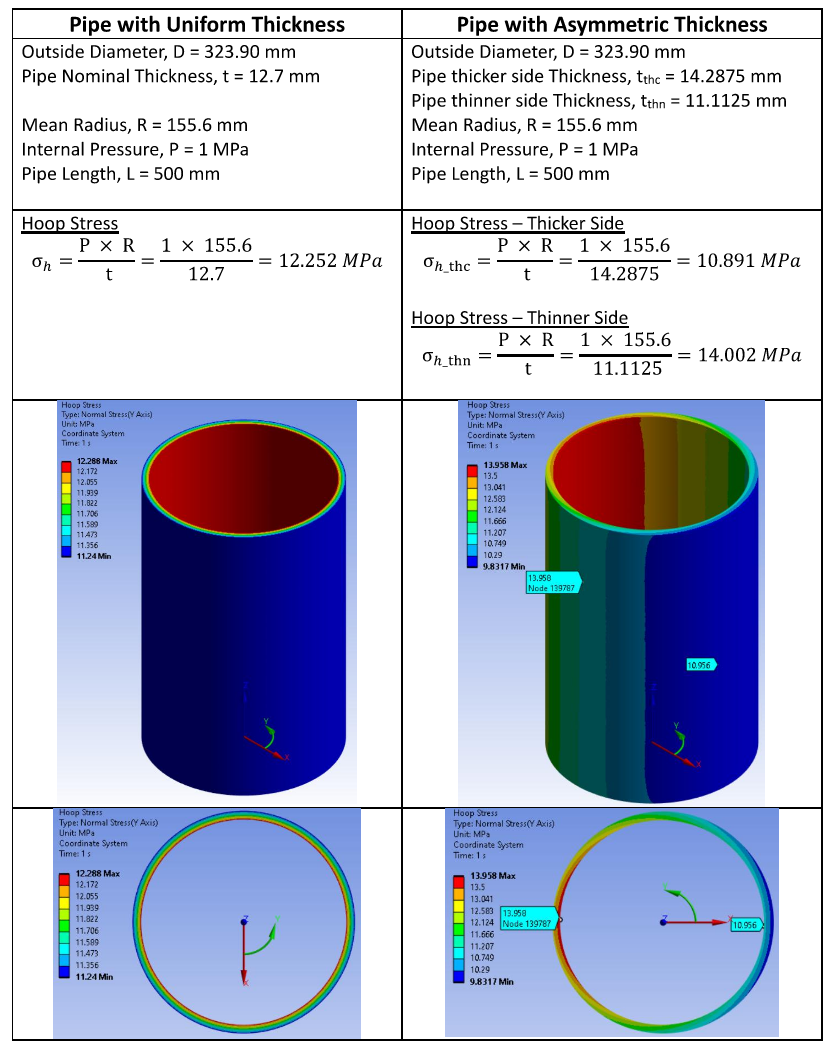

In the design of pressure vessels, particularly for nozzle-to-shell junctions, accurate assessment of local stresses under internal pressure and external loads is paramount. These regions are prone to stress concentration and fatigue, making their analysis critical. Engineers routinely use established design bulletins such as WRC 537 or WRC 297 to evaluate the stress intensification effects caused by external piping loads or internal operating pressures on nozzles.

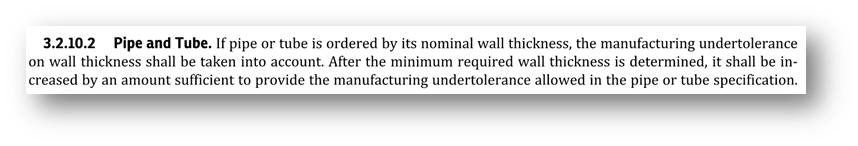

One of the key parameters used in these calculations is the nozzle neck thickness. However, engineers are often split between two choices: should the nominal wall thickness of the pipe be used? Or should the minimum pipe thickness, accounting for manufacturing tolerances, be considered?

While the difference may appear small, typically around 12.5%, this decision has direct consequences on stress results, compliance with the ASME code, and ultimately the safety and reliability of the vessel.

In this article, we will examine this issue from multiple perspectives: theoretical, practical, and code-based, with special reference to ASME BPVC Section VIII, Division 2 (2023 Edition), and the implications for WRC-based stress evaluation.